Traditionally country antique dealers stocked a good selection of brass and copper articles. In London alone there are shops given over almost exclusively to them. And yet at present, unless an article can be proved to be of earlier date than 1600 it is unlikely to have very great value. So you could start collecting brass and copper now quite easily and perhaps your heirs will ultimately reap the benefit.

Traditionally country antique dealers stocked a good selection of brass and copper articles. In London alone there are shops given over almost exclusively to them. And yet at present, unless an article can be proved to be of earlier date than 1600 it is unlikely to have very great value. So you could start collecting brass and copper now quite easily and perhaps your heirs will ultimately reap the benefit.Brass and copper have been used to manufacture household objects for centuries. Both metals reflect warmth and glow when polished. The affection with which brass and copper have been held is demonstrated by the reproduction items in their tens of thousands. Helmet shaped coal scuttles, brass and copper warming pans, copper kettles, brass chestnut roasters, clockwork brass bottle jacks for turning the roast joint, shaped copper stomach warmers and large copper containers for warming the feet while on long train journeys are but a part of the panorama of copper and brass available to the collector. While books may be consulted there really is no substitute for handling the items in order to make comparisons with copies and fakes. A copy is precisely that although most so called copies are but loosely based on the originals, on the other hand a fake is made with care in order to be passed off as an original and is therefore a far more dangerous proposition.  The warming pan is an interesting household article. It dates back to the Middle Ages when the pan was brass or bronze and it had a metal handle. James II son by his second wife Mary of Moderna, was thought by some not to be her child but a substitute brought into the royal confinement room in a warming pan. It is unlikely that it would have been a copper pan, however, for these do not appear to have come in until 1700, when they had beech handles well turned and sometimes lacquered in black. Since the advent of the hot water bottle, these pans are no longer functional but they do look attractive hung on a wall, especially if they are kept sparkling clean.

The warming pan is an interesting household article. It dates back to the Middle Ages when the pan was brass or bronze and it had a metal handle. James II son by his second wife Mary of Moderna, was thought by some not to be her child but a substitute brought into the royal confinement room in a warming pan. It is unlikely that it would have been a copper pan, however, for these do not appear to have come in until 1700, when they had beech handles well turned and sometimes lacquered in black. Since the advent of the hot water bottle, these pans are no longer functional but they do look attractive hung on a wall, especially if they are kept sparkling clean.  Perhaps the most famous article made in brass in the past was candlesticks, and this is not surprising since every house had to have lighting of some kind. Most 1600's candlesticks of brass had wide, round inverted trumpet bases. Half-way up the stem was a special candle wax catcher, for the earlier candle-holder lips were hardly thicker than the holders. Then, at the end of the century someone thought of bending the lip over at right angles outwards, so that it acted as a candle-wax catcher. A little later the lip was part of a removable tube which slotted inside the top of the stick. The centre catcher then disappeared. A stick with a catcher in the middle or thereabouts would therefore be a good find.

Perhaps the most famous article made in brass in the past was candlesticks, and this is not surprising since every house had to have lighting of some kind. Most 1600's candlesticks of brass had wide, round inverted trumpet bases. Half-way up the stem was a special candle wax catcher, for the earlier candle-holder lips were hardly thicker than the holders. Then, at the end of the century someone thought of bending the lip over at right angles outwards, so that it acted as a candle-wax catcher. A little later the lip was part of a removable tube which slotted inside the top of the stick. The centre catcher then disappeared. A stick with a catcher in the middle or thereabouts would therefore be a good find.  Another popular article for collecting is the horse brass, though it is by no means easy even for the specialist to distinguish between the 1700's and early 1800's genuine ones and the mass produced variety that has been turned out since 1880. Old horse brasses were usually fitted to the harness of the horse and should show signs of wear underneath, were they rubbed against the leather. Many also had two short pins braved on the underside with which the craftsmen held the whole brass in a vice before cutting and polishing the design. The brass had flaws, little crevices which collected dirt. But it is not very difficult to fake horse brasses and the last resort is to depend on the honesty of the dealer or the knowledge of a specialist.

Another popular article for collecting is the horse brass, though it is by no means easy even for the specialist to distinguish between the 1700's and early 1800's genuine ones and the mass produced variety that has been turned out since 1880. Old horse brasses were usually fitted to the harness of the horse and should show signs of wear underneath, were they rubbed against the leather. Many also had two short pins braved on the underside with which the craftsmen held the whole brass in a vice before cutting and polishing the design. The brass had flaws, little crevices which collected dirt. But it is not very difficult to fake horse brasses and the last resort is to depend on the honesty of the dealer or the knowledge of a specialist.

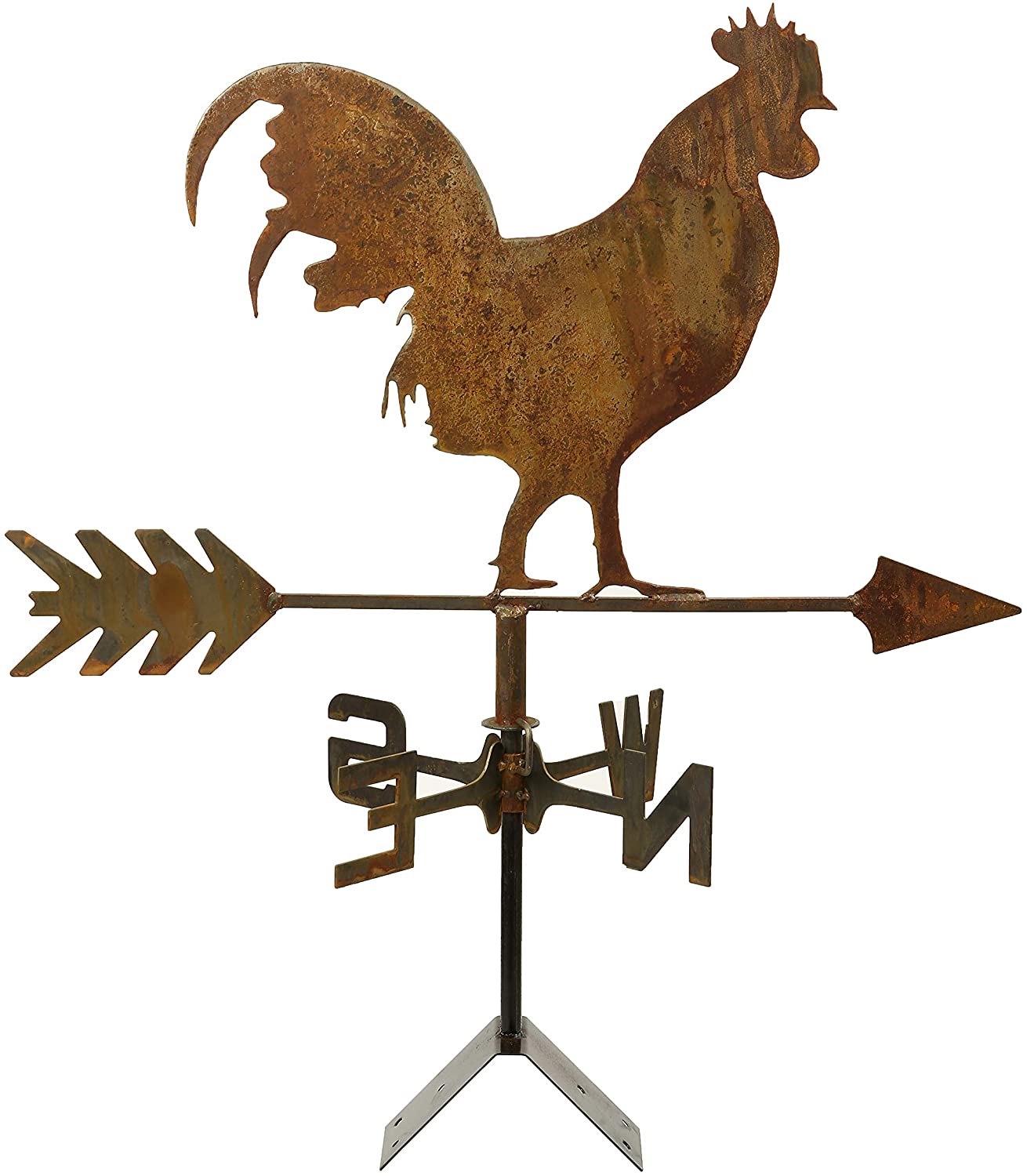

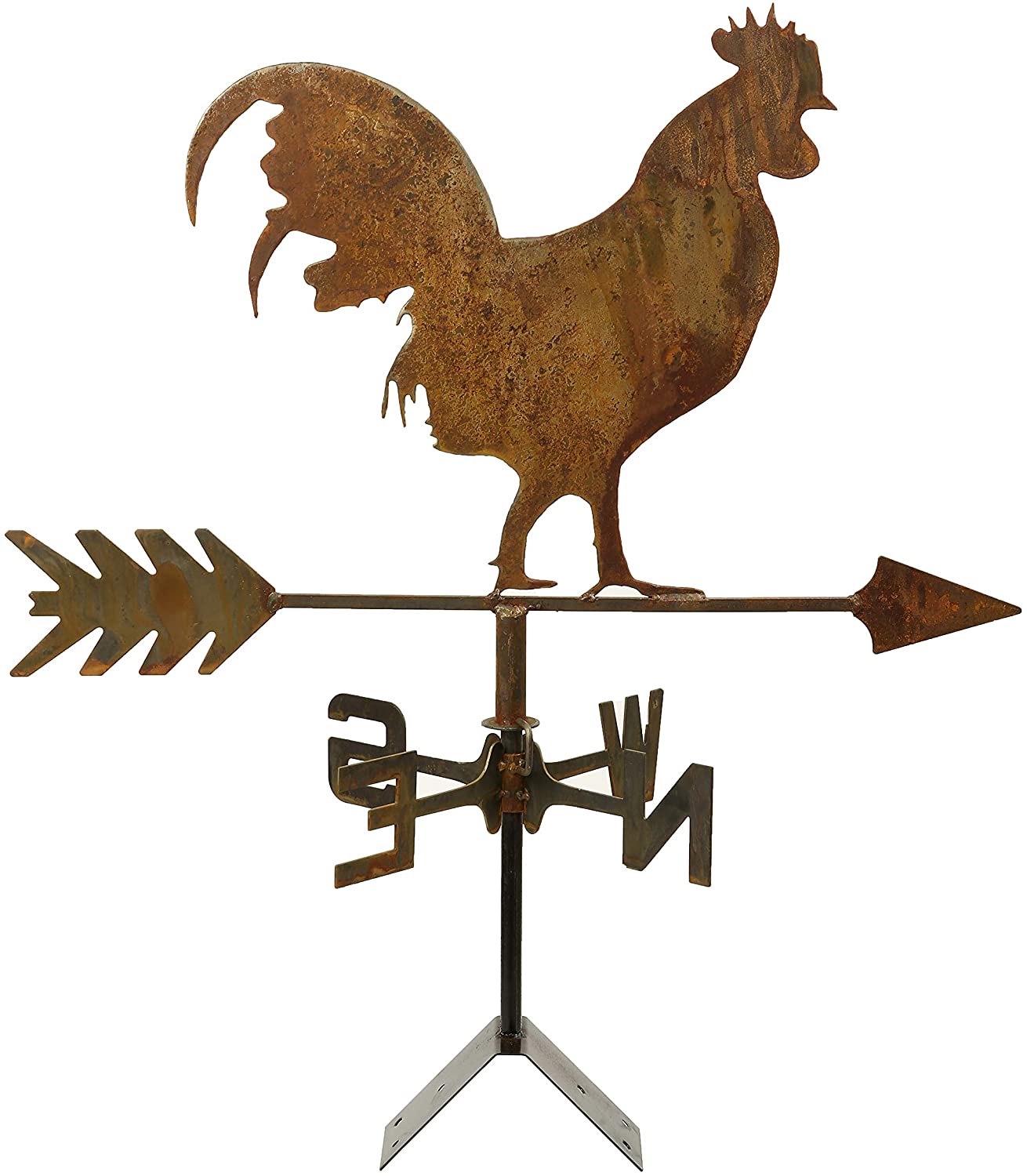

Copper collectors in America still search for 1700's and early 1800's weathervanes. These were often of two or more sheets of copper brazed together at the edges, and cut out to form the figures required, such as cockerels, fishes, ships, horses and even grasshoppers. Coppersmiths also produced with great skill those items so widely used in Britain, coal scuttles, kettles (in America they often had swinging handles) and preserving pans.

Copper collectors in America still search for 1700's and early 1800's weathervanes. These were often of two or more sheets of copper brazed together at the edges, and cut out to form the figures required, such as cockerels, fishes, ships, horses and even grasshoppers. Coppersmiths also produced with great skill those items so widely used in Britain, coal scuttles, kettles (in America they often had swinging handles) and preserving pans.

Before starting to collect copper it would be as well to clear up one or two points about the manufacturing industry. It is one of the oldest metals known to man, and it is a constituent of bronzes. The Bronze Age more or less marks the period when man first became civilized. Copper either in its natural state or as part of an alloy or mixture, has thus been in use for 6000 years at least.

In Britain upon the end of the 1600's, articles were made of thick copper beaten out with a hammer, and the colour after polishing was generally very pale. Beating was not of a very high degree of skill, and the surface of containers for example, had many flaws. At the end of the century beating techniques improved and there were far fewer flaws. The colour too became more red, but the material remained thickish. Then in about 1730, the manufacturers began to roll copper, and the resulting products were much thinner, much more red and nearly flawless. From about 1775 copper hollo-ware, that is vessels for holding liquids were sometimes stamped with ornamental designs. This was done by beating the copper from the reverse side of the sheet into specially cut dies. As the vessels were made to hold liquids for drinking or at least to reach the mouth, the poisonous copper surfaces inside were coated with tin. This was also the case with saucepans, preserving pans and such like. Early in the 1800's copper vessels were made of spun copper, that is sheet thin and malleable enough for spinning on a lathe.

It is therefore possible to give rough dates to copper articles, but a word of warning. There is not much left of copper-ware of the more ordinary household variety that is older than 1800. Most earlier pieces are in museums, and their dates can be proved. Coal scuttles for example, even if they conform to the rules, that is, are thick, pale, and have flaws, are almost always skilful mid or late 1800's copies of earlier styles. There are some specialist outside a museum or important house who state that no coal scuttle or kettle exists that can be dated before 1837.

Principal articles of copper still available, even if sometimes they are only good copies, are ale measures, saucepans, coffee pots, warming pans, candleholders (not candlesticks) and preserving pans. Naturally a variety of other articles were made such as trays, finger bowls and goblets. Ale measures came in sets from half gallon down to a dram or tablespoonful. Full sets of 1700's ale measures are extremely rare and copied sets, which are expensive can be seen in many country inns. You will notice the copper is thin and so much more dented than it need be that at first sight the copy looks like the genuine article.

Warming Pans

The warming pan is an interesting household article. It dates back to the Middle Ages when the pan was brass or bronze and it had a metal handle. James II son by his second wife Mary of Moderna, was thought by some not to be her child but a substitute brought into the royal confinement room in a warming pan. It is unlikely that it would have been a copper pan, however, for these do not appear to have come in until 1700, when they had beech handles well turned and sometimes lacquered in black. Since the advent of the hot water bottle, these pans are no longer functional but they do look attractive hung on a wall, especially if they are kept sparkling clean.

The warming pan is an interesting household article. It dates back to the Middle Ages when the pan was brass or bronze and it had a metal handle. James II son by his second wife Mary of Moderna, was thought by some not to be her child but a substitute brought into the royal confinement room in a warming pan. It is unlikely that it would have been a copper pan, however, for these do not appear to have come in until 1700, when they had beech handles well turned and sometimes lacquered in black. Since the advent of the hot water bottle, these pans are no longer functional but they do look attractive hung on a wall, especially if they are kept sparkling clean.The other metal was brass. This is an alloy of copper and zinc, the zinc being obtained for centuries from calamine mineral from Somerset or from the district around Liege in Belgium.

A considerable number of articles have been made in brass. It is harder and less susceptible to denting. But it losses its brilliance quickly, and in the old days it was given regular and frequent polishing. Old pieces therefore ought to show signs of wear which would be difficult – and uneconomic – to imitate. In about 1770 various attempts were made to protect brass from dulling, and a lacquer was developed. Nowadays cellulose can be used, but it is not recommended, unless you know that it is definitely a type that is harmless and can be removed with ease.

Medieval brass articles, such as fire dogs and ecclesiastical items such as crucifixes, plates and chalices are found extremely rarely outside museums or old buildings, and if they were obtainable, would be very expensive. But after about 1600 brass began to be made in great quantity, and like copper, can be collected quite cheaply. What is more, the variety is greater.

Candlesticks

Perhaps the most famous article made in brass in the past was candlesticks, and this is not surprising since every house had to have lighting of some kind. Most 1600's candlesticks of brass had wide, round inverted trumpet bases. Half-way up the stem was a special candle wax catcher, for the earlier candle-holder lips were hardly thicker than the holders. Then, at the end of the century someone thought of bending the lip over at right angles outwards, so that it acted as a candle-wax catcher. A little later the lip was part of a removable tube which slotted inside the top of the stick. The centre catcher then disappeared. A stick with a catcher in the middle or thereabouts would therefore be a good find.

Perhaps the most famous article made in brass in the past was candlesticks, and this is not surprising since every house had to have lighting of some kind. Most 1600's candlesticks of brass had wide, round inverted trumpet bases. Half-way up the stem was a special candle wax catcher, for the earlier candle-holder lips were hardly thicker than the holders. Then, at the end of the century someone thought of bending the lip over at right angles outwards, so that it acted as a candle-wax catcher. A little later the lip was part of a removable tube which slotted inside the top of the stick. The centre catcher then disappeared. A stick with a catcher in the middle or thereabouts would therefore be a good find.At the same time, that is in the 1700's, stick bases began to vary. Sometimes they would be square shaped with the corners cut off, or octagonal or shaped as a pattern of leaves. The stems too sported a variety of shapes, some not unlike the baluster stems of early 1700’s drinking glasses. In the classical Revival period following Robert Adam in the second half of the 1700’s, stems became square with fluting or reeding occasionally rising to architectural capitals, such as the Corinthian acanthus-leaf type. Vase-shaped stems also appeared.

It is not easy to spot the difference between genuine and fake articles, but a rough guide is that up to about 1670 the stem and candle holder were cast as one piece and attached to the base by a screw thread or tenon through the hole in the centre. After this time the two pieces tended to be brazed together at the join between base and stem. This persisted almost throughout the 1700's, and in the 1800's makers returned to making casts in one piece or to assembling candlesticks from several pieces. Moulding should have been considerably softened by years of wear and would be hard to imitate.

Horse Brasses

Another popular article for collecting is the horse brass, though it is by no means easy even for the specialist to distinguish between the 1700's and early 1800's genuine ones and the mass produced variety that has been turned out since 1880. Old horse brasses were usually fitted to the harness of the horse and should show signs of wear underneath, were they rubbed against the leather. Many also had two short pins braved on the underside with which the craftsmen held the whole brass in a vice before cutting and polishing the design. The brass had flaws, little crevices which collected dirt. But it is not very difficult to fake horse brasses and the last resort is to depend on the honesty of the dealer or the knowledge of a specialist.

Another popular article for collecting is the horse brass, though it is by no means easy even for the specialist to distinguish between the 1700's and early 1800's genuine ones and the mass produced variety that has been turned out since 1880. Old horse brasses were usually fitted to the harness of the horse and should show signs of wear underneath, were they rubbed against the leather. Many also had two short pins braved on the underside with which the craftsmen held the whole brass in a vice before cutting and polishing the design. The brass had flaws, little crevices which collected dirt. But it is not very difficult to fake horse brasses and the last resort is to depend on the honesty of the dealer or the knowledge of a specialist.Andirons

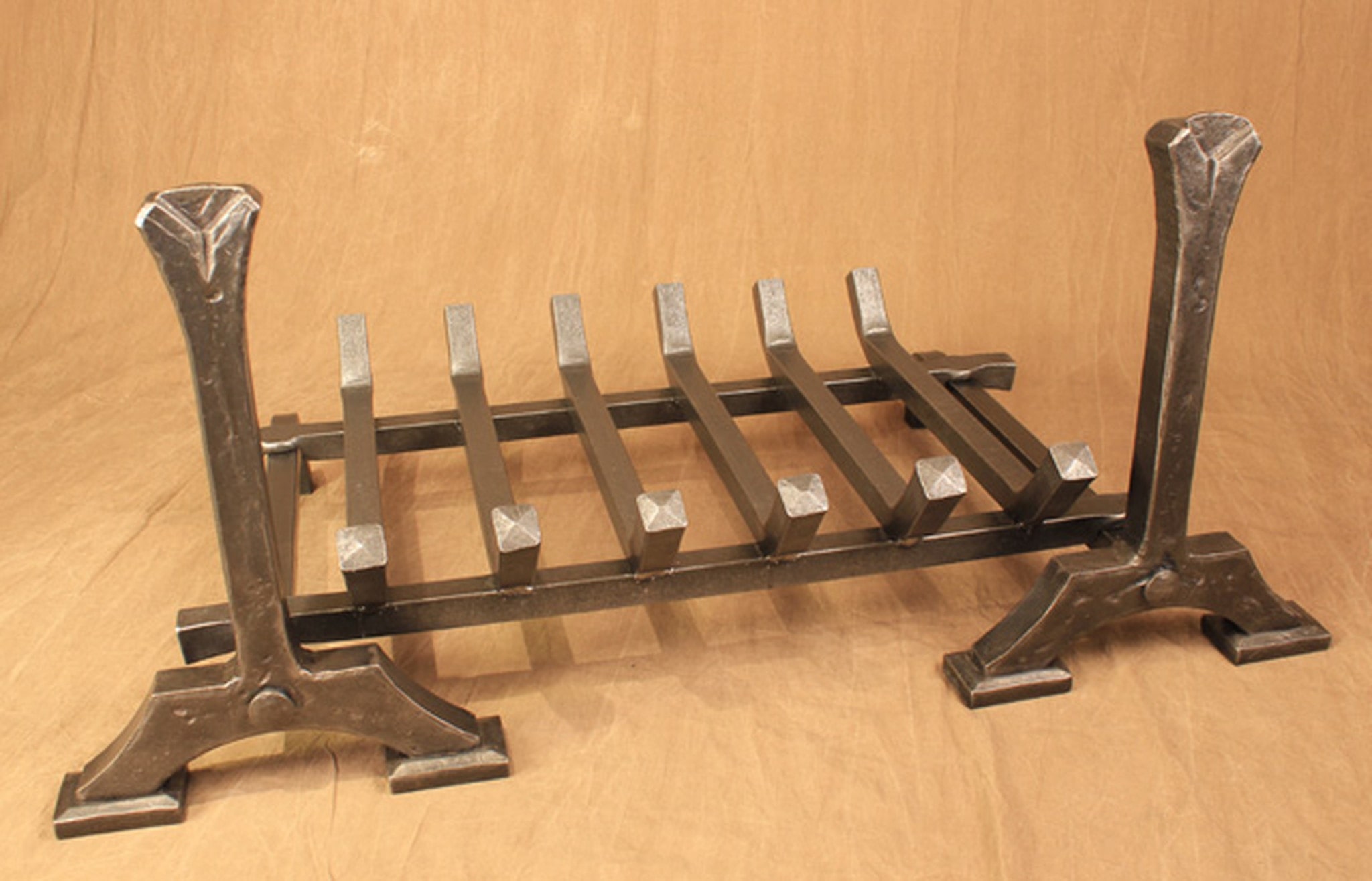

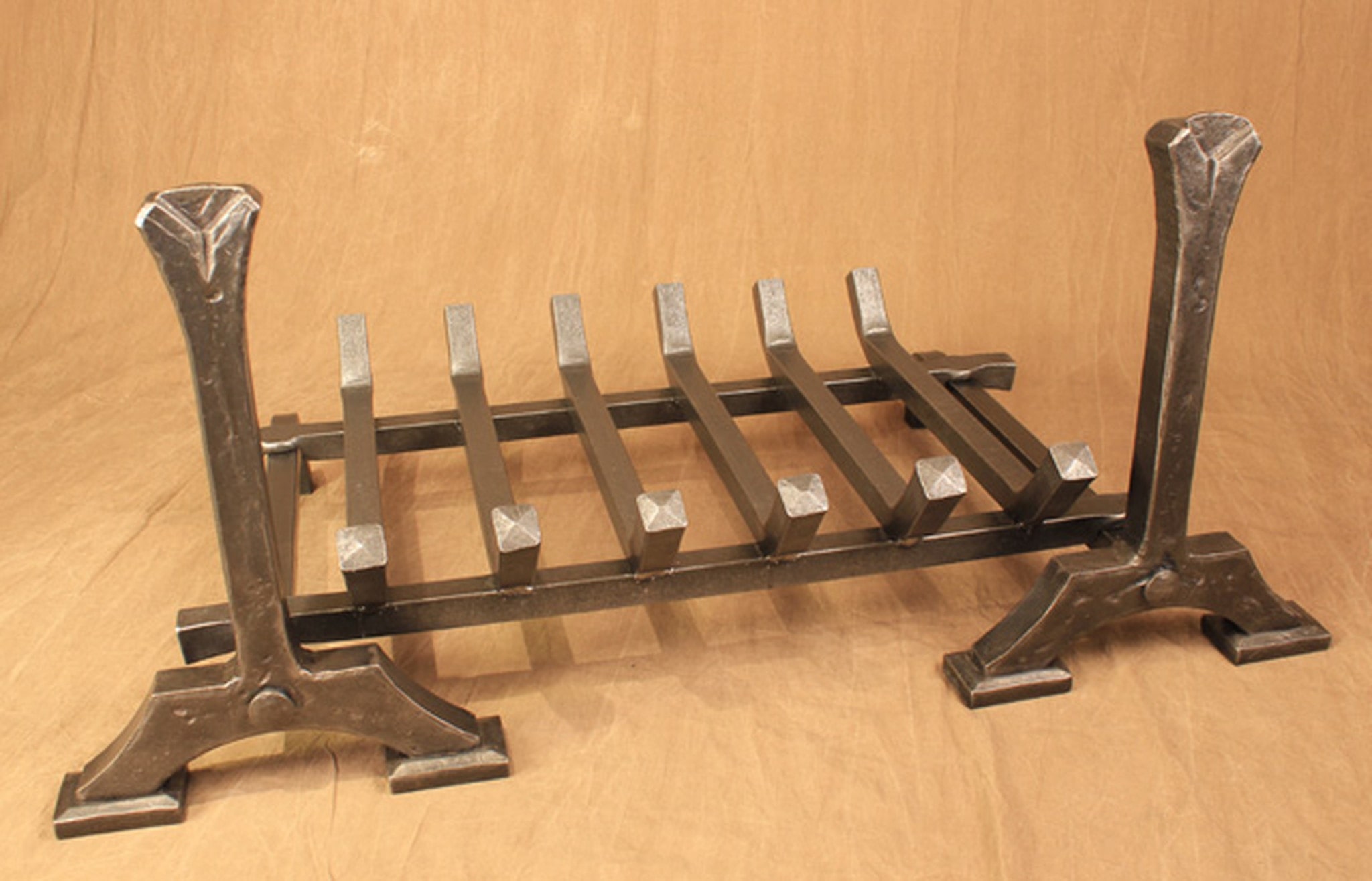

Fire dogs, otherwise called andirons, have been in use since the Middle Ages, when they were made of wrought iron. Brass came into use for decorating and surmounting them from about 1500, but the stand and the feet remain in iron. Fire dogs made entirely of brass therefore are not genuine, and were probably made in Edwardian times. In the 1700's when coal began to replace wood for heating, fenders were invented to prevent hot coal embers scattering across and scorching the wooden floor or the carpeting in front of the fire. They were made in iron, and also in brass and iron. Generally the front piece was of pierced brass supported by iron brackets and standing on an iron base plate. Many of the designs were Classical after the Adam revival. At this time too some fenders incorporated stands for the fire-irons so the need for separate dogs declined.

Fire dogs, otherwise called andirons, have been in use since the Middle Ages, when they were made of wrought iron. Brass came into use for decorating and surmounting them from about 1500, but the stand and the feet remain in iron. Fire dogs made entirely of brass therefore are not genuine, and were probably made in Edwardian times. In the 1700's when coal began to replace wood for heating, fenders were invented to prevent hot coal embers scattering across and scorching the wooden floor or the carpeting in front of the fire. They were made in iron, and also in brass and iron. Generally the front piece was of pierced brass supported by iron brackets and standing on an iron base plate. Many of the designs were Classical after the Adam revival. At this time too some fenders incorporated stands for the fire-irons so the need for separate dogs declined.

Fire dogs, otherwise called andirons, have been in use since the Middle Ages, when they were made of wrought iron. Brass came into use for decorating and surmounting them from about 1500, but the stand and the feet remain in iron. Fire dogs made entirely of brass therefore are not genuine, and were probably made in Edwardian times. In the 1700's when coal began to replace wood for heating, fenders were invented to prevent hot coal embers scattering across and scorching the wooden floor or the carpeting in front of the fire. They were made in iron, and also in brass and iron. Generally the front piece was of pierced brass supported by iron brackets and standing on an iron base plate. Many of the designs were Classical after the Adam revival. At this time too some fenders incorporated stands for the fire-irons so the need for separate dogs declined.

Fire dogs, otherwise called andirons, have been in use since the Middle Ages, when they were made of wrought iron. Brass came into use for decorating and surmounting them from about 1500, but the stand and the feet remain in iron. Fire dogs made entirely of brass therefore are not genuine, and were probably made in Edwardian times. In the 1700's when coal began to replace wood for heating, fenders were invented to prevent hot coal embers scattering across and scorching the wooden floor or the carpeting in front of the fire. They were made in iron, and also in brass and iron. Generally the front piece was of pierced brass supported by iron brackets and standing on an iron base plate. Many of the designs were Classical after the Adam revival. At this time too some fenders incorporated stands for the fire-irons so the need for separate dogs declined.Fenders

Brass fenders abound and good ones, probably early 1800's imitations can be found. It is of course difficult to determine their age, as the skill of the 1800's makers was very great.

Trivets

Another item of brass you can collect is the trivet. These were stands for kettles or saucepans by firesides. They had fittings for the bars of grates, or legs upon which the trivet could stand independently. The 1600's and 1700's forms were usually round with brass tops. They became more square with a rounded end out of which protruded a handle. The trivet was mounted on four legs. The surface was often pierced or decorated in most intricate patterns, and sometimes the plain pieces of the brass were engraved. Very little brass and copper was made in America before the War of Independence. What was needed by the early immigrants was generally imported from Europe. But as with glass and china, after the war there was a spontaneous rush to design and manufacture household and decorative utensils in brass and copper. In 1780 James Emerson fused zinc and copper in the ratio of one to two and produced a very high quality brass which had a golden hue. It was soft to beat out and could be produced in thin sheets for easy use. An Emerson piece is hard to find anywhere, but later articles, made in brass according to his formula can be picked up and are worth collecting. In 1790. The Waterbury Brass Works were opened in Connecticut, and a few years later Paul Revere, the silver expert, was designing and making a number of brass articles including fire-dogs.

Weather Vanes

Copper collectors in America still search for 1700's and early 1800's weathervanes. These were often of two or more sheets of copper brazed together at the edges, and cut out to form the figures required, such as cockerels, fishes, ships, horses and even grasshoppers. Coppersmiths also produced with great skill those items so widely used in Britain, coal scuttles, kettles (in America they often had swinging handles) and preserving pans.

Copper collectors in America still search for 1700's and early 1800's weathervanes. These were often of two or more sheets of copper brazed together at the edges, and cut out to form the figures required, such as cockerels, fishes, ships, horses and even grasshoppers. Coppersmiths also produced with great skill those items so widely used in Britain, coal scuttles, kettles (in America they often had swinging handles) and preserving pans.