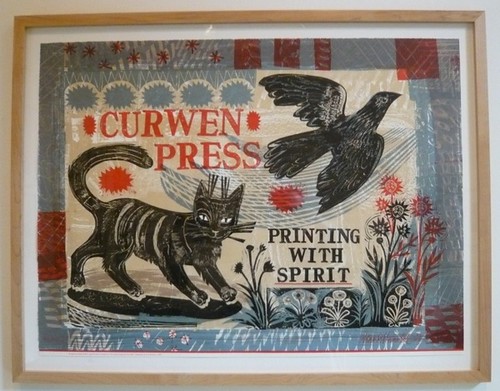

Harold Curwen and his partner Oliver Simon, ensured that the name of Curwen Press stood for quality, whether the job was a letterhead, trade label or Julius Meier Graefe's two volume work on Van Gogh.

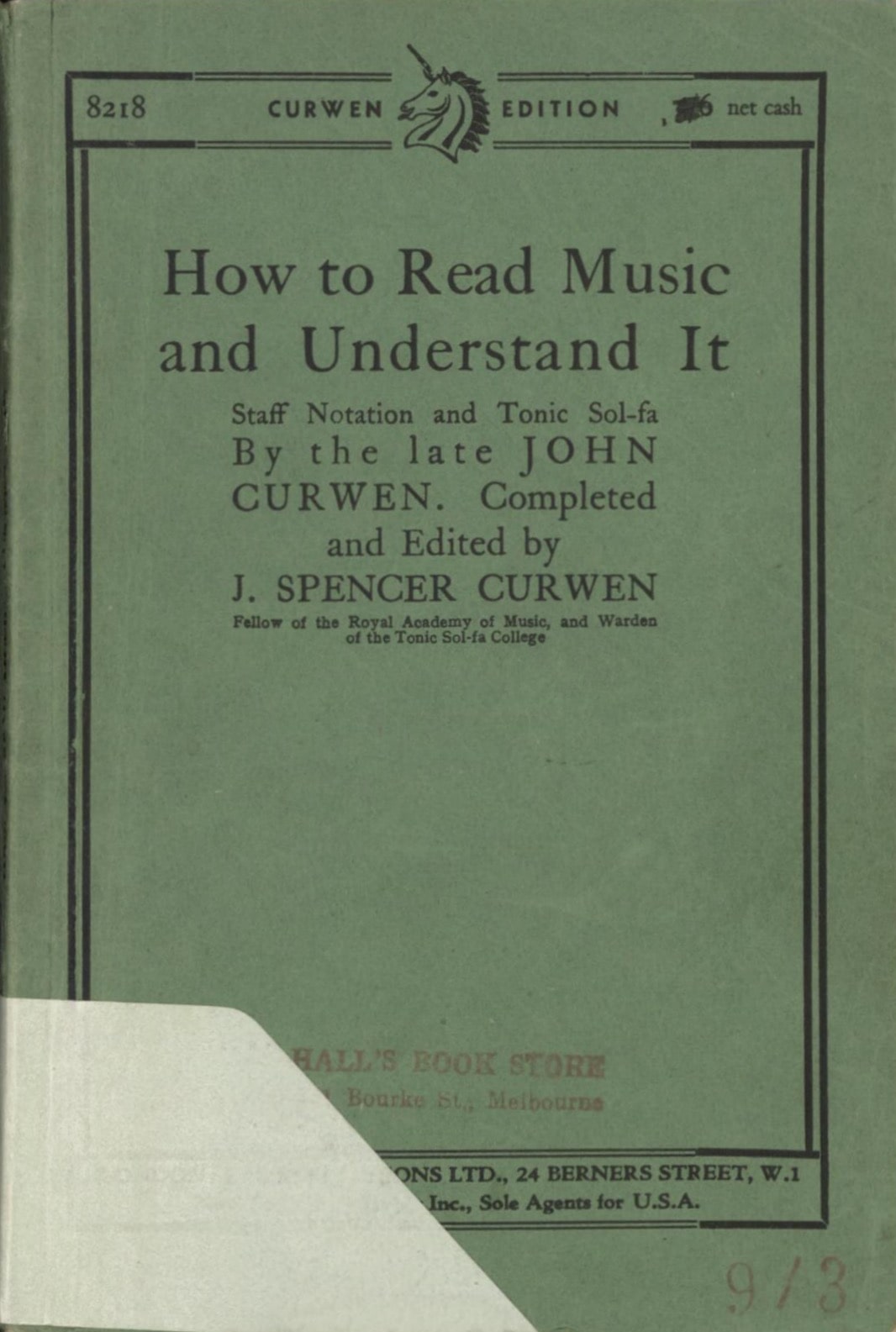

Harold Curwen and his partner Oliver Simon, ensured that the name of Curwen Press stood for quality, whether the job was a letterhead, trade label or Julius Meier Graefe's two volume work on Van Gogh. It was not always thus. The press had been founded by Harold's grandfather, the Revd. John Curwen, an Independent minister, to publish and distribute tonic sol-fa music for congregational singing, and music publishing remained an integral part of the business until 1930s.

It was not always thus. The press had been founded by Harold's grandfather, the Revd. John Curwen, an Independent minister, to publish and distribute tonic sol-fa music for congregational singing, and music publishing remained an integral part of the business until 1930s.The Revd. John had been appointed Minister to the Independent Chapel at Plaistow in 1844, but twenty years later resigned to concentrate his energies on the promotion of tonic so-fa method. During his ministry Plaistow had expanded from a rural community to become an industrial London suburb, with a consequent population explosion.

This necessitated the building of a new chapel and school, leaving the old chapel building empty, the Revd. John took this over, installed his presses and undertook the printing of The Tonic Sol-fa Reporter and Magazine of Vocal Music for the People, which until then had been produced in Suffolk. By 1864 The Reporter, as it was familiarly known, had a readership of over 180,000 and this regular monthly printing order was the bedrock of the firm of John Curwen & Sons.

With the building of the Victoria Docks, Plaistow and the surrounding area continued to expand, and to attract more and bigger business. The Revd. John's two sons expanded the press beyond its original commitment, undertaking printing for local enterprises such as the West Ham Tram Corporation, which became one of their biggest customers. The brothers, John Spencer and Joseph Spedding were by now prosperous members of the Nonconformist middle-class, intent on giving their sons a good education. Eschewing the traditional public schools, they sent them to Abbotsholme in Derbyshire, and there the young Harold learnt carpentry, printing, agricultural husbandry and first came across the ideals of the Arts and Crafts Movement.

With the building of the Victoria Docks, Plaistow and the surrounding area continued to expand, and to attract more and bigger business. The Revd. John's two sons expanded the press beyond its original commitment, undertaking printing for local enterprises such as the West Ham Tram Corporation, which became one of their biggest customers. The brothers, John Spencer and Joseph Spedding were by now prosperous members of the Nonconformist middle-class, intent on giving their sons a good education. Eschewing the traditional public schools, they sent them to Abbotsholme in Derbyshire, and there the young Harold learnt carpentry, printing, agricultural husbandry and first came across the ideals of the Arts and Crafts Movement.As a teenager Harold was in thrall to the ideals of Ruskin and William Morris, and after leaving school decided to learn the craft of printing from the shop-floor upwards.To this end he went to work as an apprentice in the family firm, then spent a year with a firm of music publishers  in Leipzig, one of the most important centres of printing. Germany was in the throes of discarding the Gothic alphabet in favour of the Roman face, with the result that they were developing a range of new printing presses. Harold studied these, making careful drawings and noting the advantages and disadvantages of each. Back in London he enrolled as a student at the Central School of Arts and Crafts to study calligraphy under Edward Johnston, so by the time he joined the staff of J. Curwen & Sons in 1908 he had a good working knowledge of the technical side of printing as well as an appreciation of letter forms and the art of writing.

in Leipzig, one of the most important centres of printing. Germany was in the throes of discarding the Gothic alphabet in favour of the Roman face, with the result that they were developing a range of new printing presses. Harold studied these, making careful drawings and noting the advantages and disadvantages of each. Back in London he enrolled as a student at the Central School of Arts and Crafts to study calligraphy under Edward Johnston, so by the time he joined the staff of J. Curwen & Sons in 1908 he had a good working knowledge of the technical side of printing as well as an appreciation of letter forms and the art of writing.

in Leipzig, one of the most important centres of printing. Germany was in the throes of discarding the Gothic alphabet in favour of the Roman face, with the result that they were developing a range of new printing presses. Harold studied these, making careful drawings and noting the advantages and disadvantages of each. Back in London he enrolled as a student at the Central School of Arts and Crafts to study calligraphy under Edward Johnston, so by the time he joined the staff of J. Curwen & Sons in 1908 he had a good working knowledge of the technical side of printing as well as an appreciation of letter forms and the art of writing.

in Leipzig, one of the most important centres of printing. Germany was in the throes of discarding the Gothic alphabet in favour of the Roman face, with the result that they were developing a range of new printing presses. Harold studied these, making careful drawings and noting the advantages and disadvantages of each. Back in London he enrolled as a student at the Central School of Arts and Crafts to study calligraphy under Edward Johnston, so by the time he joined the staff of J. Curwen & Sons in 1908 he had a good working knowledge of the technical side of printing as well as an appreciation of letter forms and the art of writing.Printing at the Curwen in those days consisted of the slog of getting the type set up and the work delivered on time, aesthetics played no part. As Herbert Simon, who became a partner in the Press in the 1930s , wrote in his autobiography, Song and Words, Visual appreciation at Plaistow was almost non existent and far from anyone being influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement it is unlikely anybody had ever heard of it. Harold had to bide his time, not wanting to upset the old and loyal hands who were dea ply distrustful of change, but he had the chance when he took over the running of the business at the out break of war in 1914. He seized the opportunity offered by the opportunity offered by the national shortage of metal, and its consequent high price, to get rid of the accumulation of over 200 different fonts, retaining for general use only, Casion Old Face, Monotype Old Style No.2 and Modern Wide No.18. Not even the most die-hard traditionalists on the staff could object to this patriotic action, though the directors of West Ham Tram Corporation were so incensed at receiving a batch of note headings printed in Caison, rather than Haddon Condensed, they cancelled their contract.

ply distrustful of change, but he had the chance when he took over the running of the business at the out break of war in 1914. He seized the opportunity offered by the opportunity offered by the national shortage of metal, and its consequent high price, to get rid of the accumulation of over 200 different fonts, retaining for general use only, Casion Old Face, Monotype Old Style No.2 and Modern Wide No.18. Not even the most die-hard traditionalists on the staff could object to this patriotic action, though the directors of West Ham Tram Corporation were so incensed at receiving a batch of note headings printed in Caison, rather than Haddon Condensed, they cancelled their contract.

ply distrustful of change, but he had the chance when he took over the running of the business at the out break of war in 1914. He seized the opportunity offered by the opportunity offered by the national shortage of metal, and its consequent high price, to get rid of the accumulation of over 200 different fonts, retaining for general use only, Casion Old Face, Monotype Old Style No.2 and Modern Wide No.18. Not even the most die-hard traditionalists on the staff could object to this patriotic action, though the directors of West Ham Tram Corporation were so incensed at receiving a batch of note headings printed in Caison, rather than Haddon Condensed, they cancelled their contract.

ply distrustful of change, but he had the chance when he took over the running of the business at the out break of war in 1914. He seized the opportunity offered by the opportunity offered by the national shortage of metal, and its consequent high price, to get rid of the accumulation of over 200 different fonts, retaining for general use only, Casion Old Face, Monotype Old Style No.2 and Modern Wide No.18. Not even the most die-hard traditionalists on the staff could object to this patriotic action, though the directors of West Ham Tram Corporation were so incensed at receiving a batch of note headings printed in Caison, rather than Haddon Condensed, they cancelled their contract.Through the Design and Industries Association, which was set up in 1915, Curwen met Joseph Thorp, a self professed publicist, who persuaded him that the Press needed a trademark, thus the Unicorn symbol was created, and thorp quickly penned a pamphlet, Apropos the Unicorn, lauding Curwen's virtues. The original unicorn was drawn by Paul Woodroffe, but over the years it was recreated by Eric Gill, Claud Lovat, Fraser McKnight Kauffer and others. Thorp had introduced Curwen to Fraser, whose psychedelic ink and bbrush drawings instantly became a recognisable part of the Press' house style.

Harold Curwen took Oliver Simon on as an apprentice in 1919,and he became a partner the following year. Simon was a nephew of William Rothenstien, Principal of the Royal College of Art, and his brother , Albert Rothenstein, who illustrated Hardy's Yuletide in a Younger World, the first of the Ariel Poems for Faber & Gwyer, which were to become a regular collaboration between the two firms, and a revised edition of The Haggadah, which was printed in both English and Hebrew.

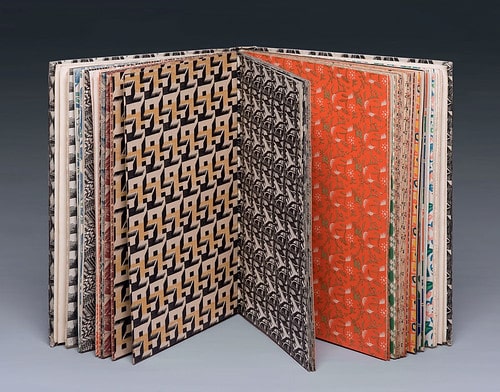

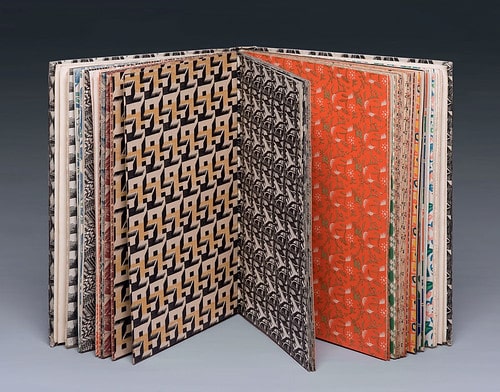

The connection with William Rotherston and the Royal College brought many young artists into Curwen's fold – Edward Bawden, Eric Ravillous, Barnett Freedman and of course Paul Nash, each of whom, in addition to illustrating books, designed pattern papers, another hallmark production of the Press. In the mis-Twenties Harold Curwen set up a pochoir studio for the hand colouring illustrations, and the next few years witnessed the publication of some of their finest books – Arnold Bennett's Elsie and the Child, and Venus Rising from the Sea, both illustrated by McKnight Kauffer, and Sir Thomas Browne's Urne Buriall and the Garden of Cyrus, illustrated by Paul Nash, which Herbert Read considered one of the loveliest achievements of contemporary English art.

The connection with William Rotherston and the Royal College brought many young artists into Curwen's fold – Edward Bawden, Eric Ravillous, Barnett Freedman and of course Paul Nash, each of whom, in addition to illustrating books, designed pattern papers, another hallmark production of the Press. In the mis-Twenties Harold Curwen set up a pochoir studio for the hand colouring illustrations, and the next few years witnessed the publication of some of their finest books – Arnold Bennett's Elsie and the Child, and Venus Rising from the Sea, both illustrated by McKnight Kauffer, and Sir Thomas Browne's Urne Buriall and the Garden of Cyrus, illustrated by Paul Nash, which Herbert Read considered one of the loveliest achievements of contemporary English art.After this, the Great Depression set in necessitating severe financial curbacks, the pochoir studio was disbanded and the business reconstituted with herbert Simon, Oliver's brother, joining the firm as a partner from the Kynoch Press. Although first-class work continued to be produced by the Press, it never again quite achieved the peaks of the previous decade.